1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia

2Department of Immunology, St Jude Childrens Research Hospital, 332 Nth Lauderdale, Memphis, TN 38105, USA

3WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza, 10 Wreckyn Street, North Melbourne, Victoria 3051, Australia

Journal of Biology 2009,

8:69doi:10.1186/jbiol179

http://jbiol.com/content/8/8/69

© 2009 Biomed Central Ltd

The 1918 pandemic influenza virus is said to have started by causing relatively mild disease in the summer but to have become more severe in the winter. Do we know why, and might influenza A (H1N1) 2009 do the same?

It is not clear precisely what changes resulted in the increased severity of infection during the second wave of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. Certainly the occurrence of multiple waves of influenza infection in the same year is unusual and one possibility is progressive adaptation of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus to its new human host

[

1].

Molecular analysis, for example, suggests that the virus that emerged during the second wave in the Northern hemisphere had undergone changes in the hemagglutinin (HA) binding site that increased binding specificity for human receptors

[

2]. This is presumed to have affected the replicative capacity and, therefore, the pathogenicity of the virus.

The 1918 Spanish influenza virus also encoded a non-structural 1 (NS1) protein capable of blocking interferon production and thus prevention of viral replication by the host

[

3]. Changes in the NS1 protein may also have contributed to host adaptation and increased virulence

[

1].

Importantly, however, two of the features that account for the virulence of the highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) viruses are not present either in the Spanish influenza virus or in the current pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus

[

4].

These are a lysine at position 627 of the polymerase basic subunit 2, and glutamic acid in position 92 of NS1 that, at least in animal models of infection, increase the replicative capacity of the virus and block host inhibition of viral replication, respectively

[

5,

6].

As the (H1N1) 2009 pandemic virus continues to spread, the opportunities for adaptation that increases virulence in the human host also increase, but the changes required for such adaptation and for increased virulence are difficult to predict and by no means inevitable

[

7].

What about the possibility that influenza A (H1N1) might recombine with other more virulent viruses?

There is some concern that co-circulation with seasonal influenza A viruses during the winter, or with highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses in countries where those viruses are endemic, might lead to the emergence of more virulent reassortant viruses

[

8].

But although occasional dual infections with pandemic and seasonal viruses have been detected during the 2009 Southern hemisphere winter, there have been no reports of emergence of such reassortants.

Might immunity built up in the course of the Northern hemisphere summer lessen the impact of the pandemic in the winter?

Those people who have already been infected with influenza A (H1N1) 2009 are likely to have generated antibody and T cell responses that will provide some level of protection against this virus for the coming Northern hemisphere winter, even if immune escape ('antigenic drift') variants begin to emerge.

There is no evidence so far for such mutants - that is, mutants in which the antibody binding sites in the HA have changed to escape recognition by specific antibody.

The likely explanation for the absence of antigenic drift to date is that the proportion of immune individuals in the community is still too low to drive the selection of such mutants.

This suggests that, despite the large number of people who have been infected, and serological and epidemiological evidence that older people are relatively protected [9,10], the number of susceptible individuals remains very high.

Use of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccines will be the most important approach to lessening the impact of the pandemic this coming winter in those countries that have access to them. Clinicians will also be able to draw on early international experience in the management of severe cases to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Animal experiments indicate that influenza A (H1N1) 2009 causes relatively severe disease, yet the human disease has been reported as generally relatively mild. How can this discrepancy be explained?

First of all, although initial reports suggest that most human cases of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection are mild, particularly in the developed world, this is somewhat misleading as the symptoms are generally reminiscent of those observed with seasonal influenza infection (fever associated with upper respiratory tract illness) and even seasonal influenza is estimated to cause 250,000 to 500,000 deaths worldwide each year.

Second, up to 40% of infected individuals present with vomiting and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, which is higher than for seasonal influenza, and while there is no evidence as yet, this may be indicative of more extensive viral replication.

This is actually consistent with three recent studies on the pathogenesis and transmission of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 in ferret models of infection

[

8,

11,

12]. All three studies showed that the pandemic strains exhibit more extensive replication in the respiratory tract, particularly the lower respiratory tract, of infected ferrets, as well as in mice

[

11,

12], non-human primates and pigs

[

11].

Moreover, Maines and colleagues were able to isolate virus from the GI tract of infected ferrets, suggesting an explanation for the increased incidence of GI distress in infected people

[

12], although no virus has yet been detected in the GI tract of human cases.

All three studies also showed that influenza A (H1N1) 2009 caused more tissue damage in the lower respiratory tract than do typical seasonal influenza strains.

So are you saying the human disease actually isn't mild?

In some cases, certainly it isn't.

It is important to note that the (H1N1) 2009 virus does cause severe infection in some people, including those who are otherwise healthy.

While some fatal cases have been attributed to secondary bacterial infections or exacerbation of other health conditions, as is commonly seen in fatal cases of seasonal influenza in the elderly,

an unusual feature of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection is severe viral pneumonitis, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome, prolonged stays in intensive care units and extended use of mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [

13,

14]. It is unclear what predisposes some people to mild versus severe complications.

And the tissue damage shown in the animal experiments? Isn't that also indicative of severity?

That is not clear for humans. Although the animal experiments show that influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection causes more extensive tissue damage than seasonal influenza infection, this could be relatively minor in humans, possibly because of the relatively low binding affinity of the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 viral HA for human receptors.

Human influenza viruses bind their target cells through recognition by the viral HA of cell surface glycoproteins that have sialic acid moieties linked to galactose in a α2,6 configuration.

When Maines and colleagues used a glycan array to compare glycan binding of HAs from influenza A (H1N1) 2009 and 1918 Spanish influenza

[

12], both showed the same binding specificity and pattern, but the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 HA bound with lower affinity than did the 1918 virus HA.

This was attributed to amino acid differences in the HA binding site. Lower binding affinity could affect the degree of inflammation and pathology caused by (H1N1) 2009 infection, so that

although the virus seems to cause more tissue damage, the pathology may not be as extensive as that seen in infection with the more virulent 1918 Spanish influenza virus or highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses.

Could the severe cases be caused by distinct variants of the virus?

It seems not: to date, viruses isolated from such patients have been indistinguishable from those isolated from mild cases.

There are, however, two recent findings that may help explain the increased pathogenesis in experimental animal models and the severe complications in a small number of infected people.

The first is that in non-human primates influenza A (H1N1) 2009 can infect and replicate in type II pneumocytes, a cell type that is found in the lower respiratory tract, where the cells, as well as expressing α2,6-linked sialic acid sequences, also express small amounts of α2,3-linked sialic acid in humans

[

15].

Second, it has recently emerged that influenza A (H1N1) 2009 HA has dual specificity for α2,6-linked and a range of α2,3-linked sialic acid sequences

[

16]. These findings suggest that the increased virulence of the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus, relative to seasonal influenza, and its capacity to cause severe disease in a small number of individuals, may be linked to an increased likelihood of replication within the lower respiratory tract.

What do we know about the transmissibility of influenza A (H1N1) 2009?

Modeling based on known global spread of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 from Mexico suggests the virus is more transmissible than seasonal influenza and has equivalent transmissibility to that estimated for previous pandemics

[

17].

Of particular interest is the rapid export of infections from Mexico due to international travel. There was a high correlation between international travel out of Mexico and reported cases of (H1N1) 2009 infection in other countries

[

17] until community transmission in other countries, such as the USA and Australia, led to spread from those sites.

Animal models, however, have produced conflicting data on the efficiency of aerosol transmission. Using an influenza A (H1N1) 2009 strain isolated in The Netherlands, Munster and colleagues demonstrated efficient aerosol transmission between infected ferrets and contact ferrets

[

8], whereas Maines and colleagues, using strains from the Mexican and Californian outbreaks, demonstrated inefficient aerosol transmission

[

12]. Itoh and colleagues on the other hand, using the same Californian strain, were able to demonstrate aerosol transmission

[

11].

While the reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, it is notable that infection with the Dutch virus induced sneezing in the ferrets, whereas Maines and colleagues did not report sneezing after infection with the Mexican and Californian strains.

Certainly evidence of transmission in both the Dutch and Japanese studies correlates with modeling that suggests the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus is efficiently transmitted

[

17].

Are there indications that mutants of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 are emerging that may affect immunity, transmissibility or sensitivity to antiviral drugs?

At this stage, little variation has been reported among any of the (H1N1) 2009 strains isolated since April 2009. No mutations have been identified in the HA that would be expected to affect binding to antibodies or affinity for α2,6 sialic acid receptors.

As noted above, this is likely to reflect the absence of sufficient population immunity to drive the selection of variants. Given how easily the influenza virus mutates, it is only a matter of time before this happens.

The antiviral drug zanamivir (Relenza) has been used in only a limited way for the control of (H1N1) 2009 and resistance to this drug has not yet been detected among pandemic viruses.

By contrast, oseltamivir (Tamiflu) has been used for treatment and prophylaxis on an unprecedented scale since the beginning of the outbreak.

To date, 22 oseltamivir-resistant pandemic viruses have been reported, mostly from individuals who had received the lower prophylactic dose of the drug.

All of these viruses contain the His275Tyr mutation in the neuraminidase protein that is known to confer oseltamivir resistance. Fortunately, there is no direct evidence as yet for transmission of resistant viruses to untreated contacts.

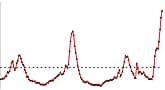

This differs from the situation among seasonal A (H1N1) influenza viruses in which a strain with the His275Tyr mutation began to spread among untreated individuals in or before late 2007

[

18] and has since become the dominant variant of that subtype circulating worldwide.

The fact that an oseltamivir-resistant strain could acquire the ability to out-compete sensitive viruses, even if this does not usually occur, has raised concern that such a variant could also emerge among pandemic H1N1 viruses.